Context

Within the Muslim community in Mombasa, Kenya, there was significant concern in the early 1980s about the increasing marginalization of Muslim children due to their limited and sometimes blocked access to primary schooling. Inadequacy in early education was recognized by parents as a barrier to future advancement in education and employment opportunities. A key issue was the existing curricular confusion and a sense of mistrust towards Western education (introduced by Christian missionaries) within the coastal Muslim communities. The Muslim communities were eager to access quality secular education to prepare their children for a better future while simultaneously preserving their values and identity, but they lacked adequate human, financial, or experiential resources in the field.

Solution

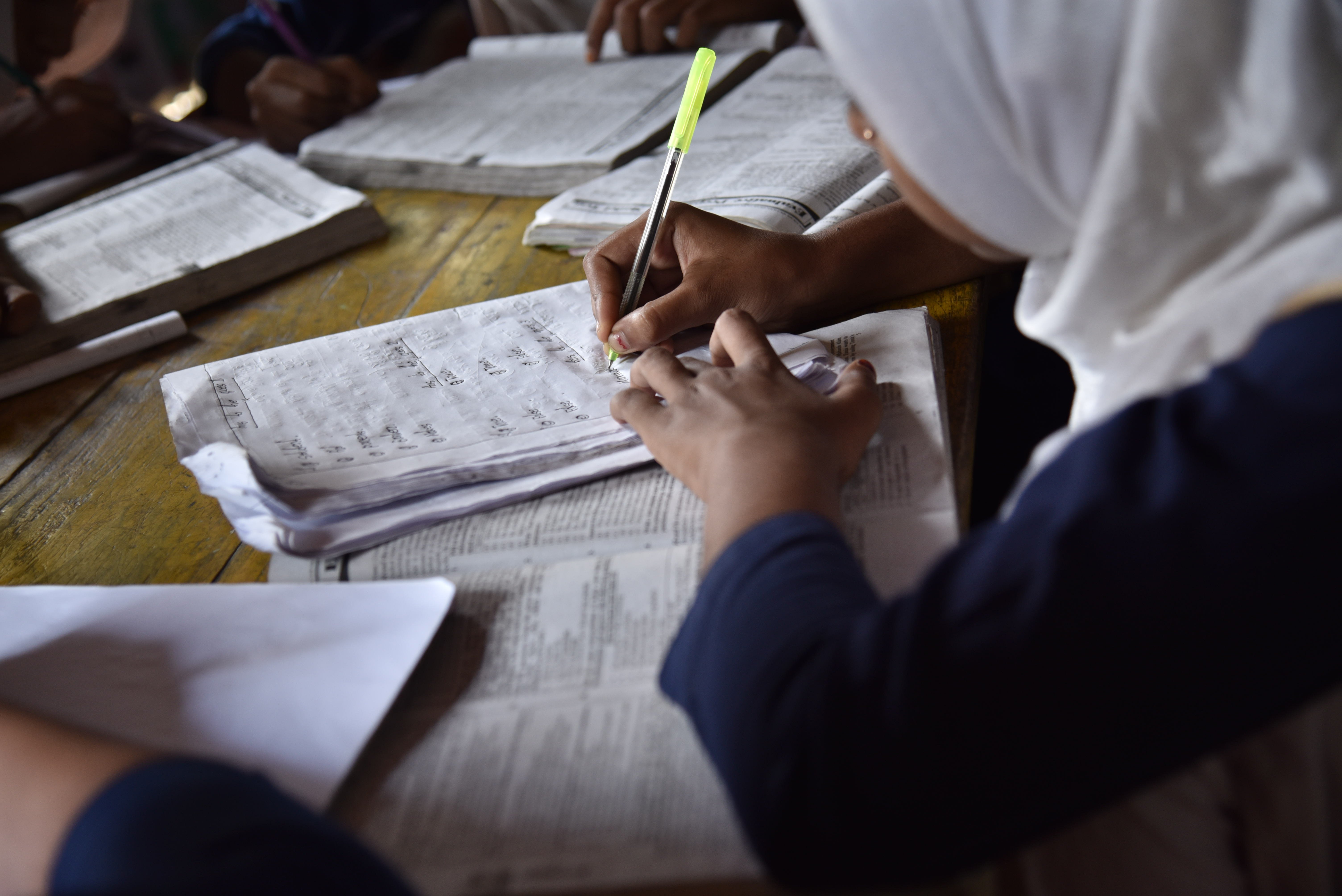

The Madrasa Early Childhood Programme (known simply as the Madrasa Programme) emerged as a direct response to these concerns. It is a project of the Aga Khan Foundation (AKF) that was piloted in Mombasa, Kenya, and later expanded to Zanzibar and Uganda. The initiative was established to facilitate the development of quality, affordable, culturally appropriate, and sustainable early childhood centers among low-income communities, particularly in poor, rural populations. It set out to help establish community pre-schools and teach children, integrating Islamic values and practices into secular pre-school education. This ensures that children receive both religious and secular education without compromising their values.

A new integrated curriculum was developed, combining Islamic knowledge and values with primary school readiness, adapting the Perry Pre-school model while incorporating local culture through language, songs, and stories. Costs were kept low by using local materials for learning resources and simple furniture. The program uses a community-led participatory model, with local School Management Committees (SMCs) managing schools and ensuring parental involvement. Madrasa Resource Centres (MRCs) serve as resource hubs, providing teacher training, curriculum development, workshops, and ongoing mentoring. Over time, the program expanded to include health and nutrition, transition support to primary school, and outreach training for other educators and NGOs, ensuring quality early childhood development in low-resource settings. Monitoring tools and structures like Graduate Pre-school Associations and Community Resource Teams support collaborative fundraising, quality review, and management, with pooled grants invested to help cover costs, including teacher salaries.

Impact

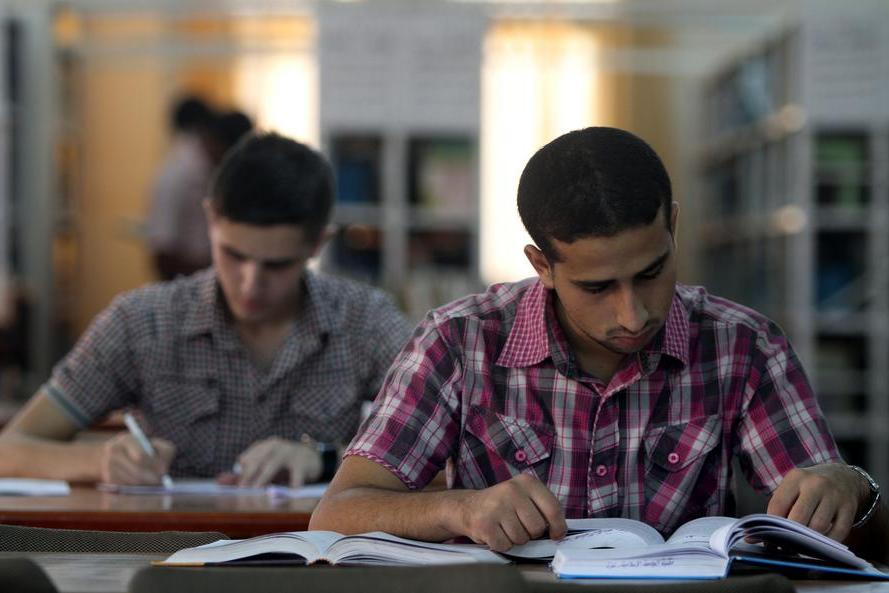

The Madrasa Early Childhood Programme has greatly improved early learning outcomes among disadvantaged communities in East Africa. A regional impact study (1999–2005) with Oxford University support found that children attending Madrasa preschools scored much higher on cognitive development tests than peers in non-Madrasa preschools or at home, with the impact of attending a Madrasa preschool more than double the impact of other preschool options. Teaching quality and enriched learning environments were key drivers of this success, with Madrasa graduates in Mombasa ranking in the top 20% up to Standard 4.

By 2008, the program had helped establish over 200 community preschools and educate 67,000 children. It also strengthened education system efficiency by improving school readiness. Beyond academics, it activated strong community ownership, offered career opportunities for marginalized young women, and demonstrated inclusivity by enrolling up to 22% non-Muslim children in some regions.

More recent figures (as of 2024) show the program reaching 10,000 children annually, training over 8,000 teachers, and impacting over 1 million children directly and indirectly. Graduates have gone on to become doctors, teachers, and community leaders, crediting the program for laying a strong foundation. The program has also contributed to national early childhood policy in Kenya, Uganda, and Zanzibar, with its curriculum influencing government frameworks. However, given that much of the rigorous evaluation evidence is older, a more up-to-date impact assessment would be valuable to confirm sustained effectiveness at scale.